From kerosene to glow worms – interpreting the Wolgan Valley Railway and the Glow Worm Tunnel

—Naomi Parry Duncan, President PHA NSW/ACT

Being a professional historian takes you places you never imagined going, such as standing outside the Sunday service of All Saints Anglican Church in Ainslie, ACT, recording a creaky old bell, for a project set in Newnes, NSW. Going down rabbit holes is one of the best parts of this job, especially when it allows you to solve questions you’ve long wondered about.

In May this year the Blue Mountains branch of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) asked me to write interpretation for the Glow Worm Tunnel Precinct. This area, on Wiradyuri Country and in the Lithgow LGA, is one of the jewels of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and Wollemi National Park. The Glow Worm Tunnel is a 387-metre railway tunnel that has been colonised by thousands of glow worms (Arachnocampa richardsae) and is a tourism drawcard, attracting 50,000 visitors a year. NPWS has recently completed a track upgrade that improves the visitor experience and protects the glow worms by providing a better path through the tunnel and a handrail so people no longer crash into the walls. They wanted new signage, an audio tour, and a video tour to augment the visitor experience.

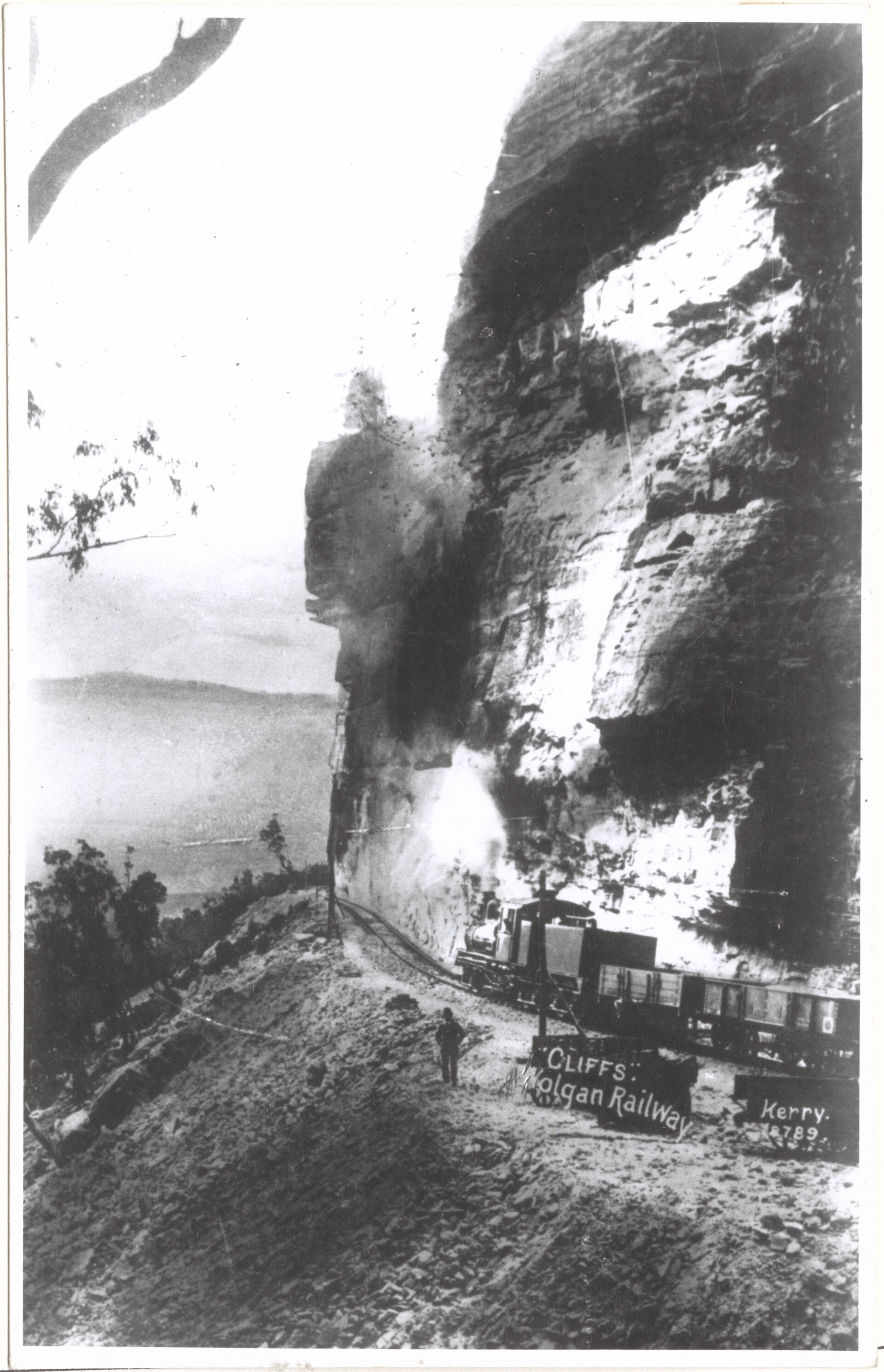

The tunnel is also a significant piece of industrial heritage, because it was cut in 1907 to serve as Tunnel No 2 of the Wolgan Valley Railway. This was an audacious rail project that linked the Commonwealth Oil Corporation (COC) oil shale (kerosene) works at Newnes in the Wolgan Valley with the Great Western Railway on the plateau above. It required cutting 51-kilometres of line into soaring sandstone escarpments, pagoda rock formations and diatremes (volcanic pipes). The COC hired a former NSW Government railway engineer, Henry Deane, who designed a brilliant system of five-chain curves, cuttings and tunnels and managed punishing gradients with US-made Shay ‘sidewinder’ steam locomotives. It was laid in 13 months, from 1906 to 1907 and 800-men and their families lived along the line in canvas cities, for the duration. Four lost their lives in accidents cutting the tunnel. This engineering marvel was wasted on the COC, which proved to be terrible at mining and producing kerosene and soon collapsed. The line was abandoned by the 1920s and the line ripped up during World War II but the main tunnel created ideal conditions for glow worms, which love dark places with running water.

Interpreting the site required a lot of thinking about the audience. Glow worms are alluring, so the natural history elements needed to be presented clearly, and NPWS also needed to offer advice on how to approach them without harming them (they are tougher than you would think, but they don’t like bright lights, smoking or vaping, or, funnily enough, being squashed by clumsy hikers). Some visitors come to see the remnants of the Wolgan Valley Railway while others simply come to bushwalk in the incredible surroundings and don’t see the drill marks on cliff faces, or notice their path is an old railway bed. Trying to meet all their needs was a challenge.

Writing interpretation for this site required a level of ingenuity that approached Deane’s (though not as many explosives). I had a pile of glass plate negatives, fewer than 5,000 words spread over a dozen or so signs, and a detailed secondary literature on shale mining, shale railways and Shay locomotives. The glow worm experts, particularly David Merritt of the University of Queensland, provided what I needed to tell the stories of the bioluminescent cannibal worms. But, having worked in Lithgow for more than 15 years, I still had big questions about the site itself, and I knew railway history buffs are an exacting audience who notice every incorrect factoid. Still, I felt the bigger picture was missing. Why did the mines fail? Why did the railway fail and where did it go? Who lived and worked alongside the railway?

Penrose Gully, Glow Worm Tunnel Precinct, 2024, Naomi Parry Duncan

This is where the social history and heritage skills of a professional historian come into play. The Wolgan Valley Railway is a story of the follies of fossil fuel hunting capitalists, who pushed a railway through wet and unstable terrain, to hunt a product that cost an enormous amount to produce both in terms of money and environmental damage. They employed hundreds of men who were prepared to raise their families in canvas tents in the cold, to chase some of the best mining and railway wages being paid in the world. And it is also a story of what might happen as the world transitions away from fossil fuel and allows the natural environment to recover (although that quote from me hit the cutting room floor).

It was such a fun project, featuring incredible site visits and the joys of working with my wonderful designer friend Judith Martinez Estrada and producer Caro Ryan. I picked a ‘heroine image’ for each sign – the one accompanying this story we call ‘Hot Miners’. You can see why.

And I also heard the All Saints Church bell. All Saints itself is special, as it was once a railway station at Rookwood Cemetery that was moved, stone by stone, to the new capital. Its bell belonged to Shay No. 1 ‘Constance’, the first locomotive brought to Australia by the COC. She ended her days on brick pylons, serving as a boiler for electricity, but in 1925 her bell was sent to Clyde Depot, where it was the fire alarm. When Clyde Depot was dismantled in 1954, the bell was donated to the NSW Steam Tram and Railway Heritage Preservation Society, who gave it to All Saints in 1958. That creaky old bell tells a story of lost dreams and reckless capitalism, and of new life from old things.

If you visit the Glow Worm Tunnel Precinct, download the (soon-to-be available) audio tour which features the sound of that bell and enjoy learning about five-chain curves and weirdly vicious worms, in an awe-inspiring landscape. And hot miners.

Image caption: Mine and railway workers at Stammers Hotel, Newnes, 1907, National Library of Australia.