Vandemonians: The Repressed History of Colonial Victoria

I suspect that few readers will be aware of the complex set of outcomes for the ex-convicts from the south. Indeed, rectifying this lack of awareness is the impulse behind this work … I believe that Vandemonians is a telling example of how traditional research methods can be married with genealogical databases to trace the course of an individual life.

READ REVIEW

↓

Vandemonians:

The Repressed History of Colonial Victoria

Janet McCalman | 2021

Janet McCalman’s Vandemonians tells the story of the thousands of convicts who travelled from Van Diemen’s Land to make a new life in the ostensibly free colony of Victoria. The book is the result of deep research, demographic analysis, detailed life studies, and, importantly, sympathy for its subjects. It is written in the author’s typical style with her taste for punchy expression, like of a good story, and subtle use of health and criminal records and vital statistics. Vandemonians draws on the work of the Ships Project, in which volunteers traced the lives of each convict on a particular transport, the vessel which would continue to act as a major identifier in the lives of its passengers in Australia. Professor McCalman used similar demographic techniques in her later Diggers to Veterans project, a study of the 1st AIF and an initiative with which I was once associated.

I suspect that few readers will be aware of the complex set of outcomes for the ex-convicts from the south. Indeed, rectifying this lack of awareness is the impulse behind this work. What a contrast it is. Van Diemen’s Land with Port Arthur, cannibal convicts and prison architecture. Victoria – where European settlement owes so much to ambitious Tasmanians – had the gold rushes, Marvellous Melbourne and no convicts. Well, that’s the accepted story, for not only did we Victorians have the Vandemonians, but we also had the ticket of leave transportees from Britain known as the Pentonville exiles. Lilywhite South Australia we are not. And, as might be expected, in those dim days past when I was a school student the convict thread in Victoria’s colonial history was not mentioned. Eureka and colonial liberalism were though. A lot.

What are the features which impress me in this work? Firstly, the sustained research that went into revealing the lives of the former convicts who too often ended up back inside a cell in Victoria. Secondly, there is the dismal evidence that if you start out sad, bad, mad or deprived, with a shattered family background, you also stand a good chance of recidivism and eking out your days in a benevolent asylum or a prison. This analysis of how adverse life circumstances affects people throughout their lives is profound and moving. Interestingly, Andrew May in his commendation of this book stated that it ‘provides salutary historical lessons for the ways in which contemporary carceral practice deals with the fractured lives of the vulnerable and the traumatised’. Sage words given that Victoria’s prison population has soared without sufficient justification from the contemporary crime rate.

I believe that Vandemonians is a telling example of how traditional research methods can be married with genealogical databases to trace the course of an individual life. As Robyn Annear wrote in her review of the book, Janet McCalman focusses ‘on those who came to Victoria, expertly balancing the micro and the macro’. Having said that, I feel that on occasion the beautifully resuscitated lives of the Vandemonians are so completely described that the main line of the narrative is temporarily obscured. My only other semi-whinge is that there are several generalisations that could be questioned or need to be fleshed out more. For example, the author claims that Methodism ‘was the most successful religious movement on the frontier’. That might be news to Irish Catholics, Presbyterian Scots with their country’s ardent belief in education, and those missions catering to Indigenous people.

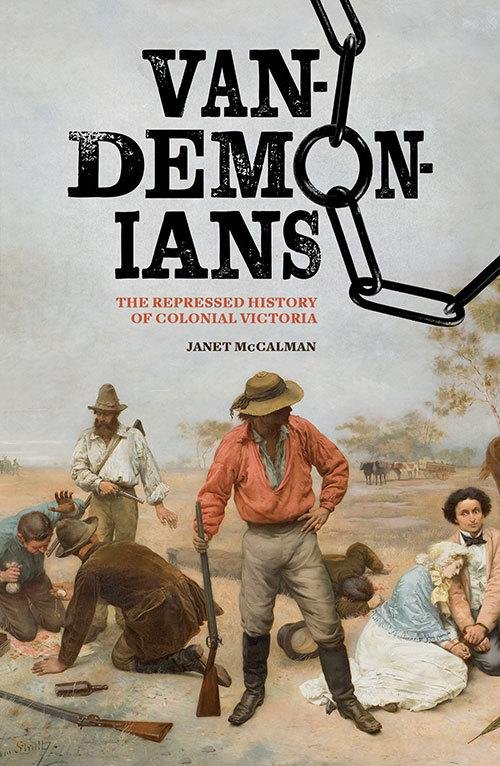

Vandemonians is a handsome looking publication, typical of the Miegunyah Press, though given this volume is a paperback, it is cheaper than many of their previous efforts and is therefore more accessible to potential readers. It is adorned with a beautifully reproduced image of William Strutt’s Bushrangers painting, which evokes the notorious robberies on Brighton Road in October 1852. But you can’t pin Vandemonians for this one – nobody was ever convicted.

Reviewer: Richard Trembath, PHA (Vic & Tas)

Vandemonians: The Repressed History of Colonial Victoria is published by The Miegunyah Press.