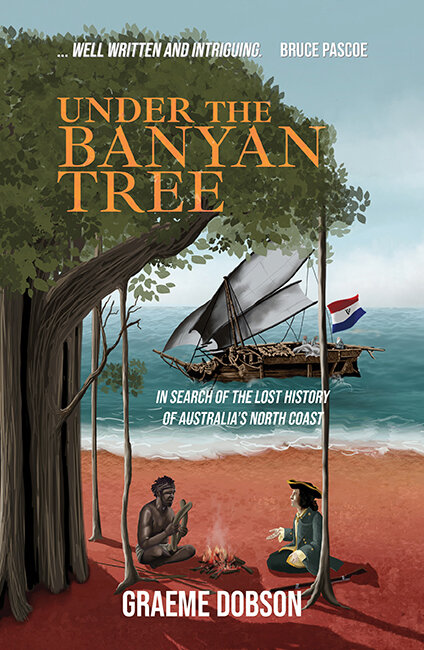

Under the Banyan Tree: In search of the lost history of Australia’s North Coast

Under the Banyan Tree is not about the botanical species. Instead, it is the account of a journey through our nearest northern neighbours – nations that rarely appear in Australian histories – and stories of trade with the Yolngu in Arnhem Land. The book offers a swashbuckling romp through changing cultures around the region.

READ REVIEW

↓

Under the Banyan Tree:

In search of the lost history of Australia’s North Coast

Graeme Dobson | 2021

The banyan tree, although now considered native to northern Australia, initially came from the Indian sub-continent, a traveller that took root in the past becoming a sacred symbol for many, and just one curiosity in the pre-colonial environment of the Yolngu people.

Graeme Dobson, a marine biologist, first became interested not in the banyan tree but in a clearly man-made offshore rock pond set 100 metres away from the shore at Warruwi settlement on Goulburn Island in the Arafura Sea off Arnhem Land. He quickly creates a list of possible culprits – missionaries, European settlers, Makassans, Baijini, Wurruwala, or other Indigenous clans. From there, he embarks on answering questions about its origin and use – neither of which are clear to him – and ventures into the fields of history and archaeology.

The pond, to Dobson’s surprise, is lined with clay, creating a permanent structure in the constant oceanic tides. Dobson questions his Yolngu guides about the pond and receives only a cryptic response. This, as much as the pond itself, sets him on a journey that takes him throughout the regional area to the Moluccas, Banda Sea, Flores Sea, Timor Sea and back to the Arafura Sea. Alongside his physical travels, Dobson engages in a search through the Northern Territory archives and libraries.

Fleets from multiple places were all visiting Arnhem Land long before 1770. Dobson shows that people have been arriving, staying for extended periods, engaging Yolngu in trade and transfer of technologies and knowledge, enlisting local people into growing and processing a range of products, and then leaving again. Some of these eras of exchange lasted a few years; others lasted for centuries. Such is the harsh and unforgiving nature of Yolngu country that very little physical material remains as evidence of these forays. A bit of broken pottery here, some buried charcoal there. And that’s it. This makes the pond unusual, to say the least.

Dobson’s goals are two-fold: to identify the people who visited, bringing with them technology to build a pond and to understand what the pond once contained. In the end, he lands on the processing of sea cucumbers, most likely by southeast Malukans, between the 16th and 17th centuries. Like other rock enclosures in locations around the region, the pond was probably used to house and grow the sea cucumbers. When enough were accumulated, they were processed in bulk according to Sasi Trepang drying methods, to become trepang. These preserved animals were then taken to markets across the region.

Dobson moves from island to island, and from east to west and north to south, to investigate places such as Ternate and Tidore, Banda and Timor Laut. Along the way, he explores the geopolitical history of each location, examining its people, politics, trade, and maritime power. Although he occasionally wanders away from the main story, Dobson ensures he always returns to the Yolgnu and the out-of-place rock pond. In doing so, he works the evidence in ways that show how some findings are logically eliminated or remain as clues within the quest.

Dobson’s account is enthralling, piecing together a regional history of travel, trade and interactions that are centuries old. He has selected a style and tone that might be described as a romping yarn; it has a boys’ own adventure feel to it. For the most part, this works to keep the narrative moving and the pace lively. However, occasionally, it reveals a belittling attitude to the people he meets along the way, which appears as mistrust of locals relaying information about their own histories. When Dobson gets to the end and returns to assess the beginning of his search, he realises, if he had listened more carefully, Yolngu knew all along who had been in their land and what they were doing.

Reviewer: Jodi Frawley, PHA (NSW & ACT)

Under the Banyan Tree is published by Boolarong Press.